How Rahul Gandhi Falls a Victim of Circumstances by using the Word Panauti

Rahul Gandhi addressed two rallies in Vallabhnagar in Udaipur and Baytoo in Balotra ahead of the November 25 Rajasthan State Assembly elections. On November 21, after India’s World Cup loss, Gandhi said at an election rally in Baytoo in Balotra, Rajasthan “Panauti… panauti…Achha bhalaa hamare ladke wahaan World Cup jeetne waale the, par panauti harwaa diya. TV waale ye nahin kahenge magar janta jaanti hai (Our boys were going to win the World Cup, but panauti got them defeated. TV channels will not say this but the public knows).”

Rahul Gandhi used Panauti to attribute India’s failure to win the India vs Australia, ICC Cricket World Cup 2023/24 Final at Narendra Modi Stadium, Ahmedabad on November 19, 2023 as a consequence of the presence of someone who was harbinger of misfortune. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was present at the stadium.

Should Rahul Gandhi have used the word Panauti to describe the outcome of a situation? Those who applaud Rahul Gandhi assert his right to do so in the context of the continuous and sustained vilification campaign unleashed by the BJP in tarnishing his public image and credibility. BJP and its machinery and its supporters have given Rahul Gandhi the pejorative name, Pappu. Though the word originally refers to a loving child, its meaning has been distorted by the BJP stalwarts and social media used it in a derogatory sense to denigrate Rahul Gandhi as an inept, under-intelligent, child-like, foolish and incapable person to lead the country and to challenge Narendra Modi.

Attack on Rahul Gandhi naming him as Pappu, which started during the election campaign in 2014, which brought Narendra Modi to power, continues even in 2023. Kiren Rijiju, BJP Minister of Law wrote on his [‘X’ on March 8, 2023](https://twitter.com/KirenRijiju/status/1633524172025663490?lang=en), “People of India know Rahul Gandhi is Pappu but foreigners don’t know that he is actually Pappu. And it’s not necessary to react to his Foolish Statements but the problem is that his Anti-India statements are misused by the Anti-India Forces to tarnish the image of India.” He was reacting to Rahul Gandhi’s criticism of Government of India in his speech at Cambridge University, UK. Rijiju called him ‘self-declared prince of congress’. In 2014, during election rally in Amravati, Narendra Modi called Rahul Gandhi ‘Shehzada’ in a ridiculing way and asked, “Does the shahzada know the pain of sleeping without shelter on cold nights.” On an election rally in Madhya Pradesh on November 14, 2023, Prime Minister Narendra Modi mocked Rahul Gandhi, calling him ‘murkhon ka sardar (leader of fools)’ over his remarks on China-made mobile phones.

Given this persistent attack on him, it has been argued that Rahul Gandhi has a right to defend himself. If they can engage in calling names and use derogatory terms, why not Rahul Gandhi? There lies the problem. When the Congress leader indicated that Prime Minister Modi has been a Panauti in the Cricket Stadium, he was in fact replicating the logic of ‘whataboutery’, which the ruling party loyalists have been accused of adopting to justify their actions.

By calling the adversary using names with implied derogatory connotations, Rahul Gandhi might get applause from the listeners, but he is not elevating the level of consciousness of the listeners and those who applaud him. What India needs now is a leader who does not stoop down to the level of the ruling party and its supporters but those who could emancipate people from the cognitive morass. Rahul Gandhi, in a way had been falling into the trap set by his adversaries.

There is another implication. The word Panauti, in Indian languages, means ill omen. It refers to a situation in which the presence of a person brings bad luck or misfortune. The search for the meaning of Panauti necessarily takes us to cultural and social behaviours which has deep roots in non-verifiable beliefs and traditions – as in the perception that a black cat crossing you will bring you bad luck.

Panauti is a perception, which cannot be objectively verified. It is a mind game which can orient people to a particular course of action, which can be extremely insensitive to the perpetrators and the recipients. However, these actions in itself will not make the perception empirically verifiable.

Current political dispensation is bringing in uncritical religiosity as the prevailing consciousness of Indian people. The ruling classes have succeeded in cementing the common sense of the people based on Hindu revivalism. More than the masses, the Indian middle classes, who are constituted largely by high castes, professionals and the business community, have internalised this religiosity. On the other side, this has a cascading effect on all religions in India, whose leaders are becoming revivalists in the pursuit of defending their spaces, in the process, creating for masses a competing but common space of blind faith relying on myths, traditions, practices, messianic leaders and which denies mutual respect and critical thinking.

The concept of Panauti does not have a scientific basis. When Rahul Gandhi, a person who should espouse a counter temperament to the prevailing one, uses a word like Panauti and attributes it to his political opponent, he is actually becoming a victim of uncritical common sense and religiosity. Instead of igniting a counter consciousness, he, in effect, reinforces the prevailing degenerative common sense of the masses.

Rahul Gandhi had befallen a victim of circumstances and failed to project himself as a leader with critical emancipatory values and perspectives.

‘Jawan’, the Super Hero and the Vicarious Satisfaction the Indian Middle Classes Experience

J John

The Shah Rukh Khan film ‘Jawan’, was released for theatrical shows on September 7, 2023. [Within 19 days](#), it amassed more than Rs.1000 crore in box office collection globally and crossed Rs.566 crores in India. Red Chillies, its production house released these figures. Jawan is competing in box office collection with others in the league – Dangal with 1970 crores, Baahubali 2: The Conclusion with 1800 crores, KGF Chapter 2 with 1230 crore and RRR with 1241 crores gross.

Atlee, Director of the film, has created a storyline coalescing a contrived world of realism with a phantasmic superhero who coerces accountability from bankers, industrialists and political leadership and reminds citizens to use their power to vote.

In a dystopian world, Shah Rukh Khan (Azad) arrives as the ultimate personage to save the world performing ‘sanitised’ violence. He also undergoes excruciating suffering as acts of heroism by the redemptive superhuman. Shah Rukh Khan engages in dazzling dances at all opportune moments. Among the most spectacular being his (Jail warden’s) dance with the female inmates. The action defies logic at all times – when the vigilante group captures whole train or when the group attacks the convoy of trucks loaded with money or when the senior Shah Rukh Khan makes his unbelievable escape from the aircraft.

Rarely does the film demands acting from the characters, they are only expected to stage-manage. Nayantara (Narmada) tends to behave like an actress. Soon the prominence shifts to Deepika Padukone (Aishwarya), who matches Shah Rukh Khan in phantasmagoric performances, this time, with his avatar as Azad’s father, Captain Vikram Rathore.

The film is well within the nationalistic discourse as in the case of most of the popular action thrillers of contemporary India. Soldier is the redeemer not only at the borders but also of issues within the nation.

Jawan raises many social, economic and financial issues – children dying in a hospital due to lack of oxygen, faulty army weapons and dangerous factories near residential areas and influencing voters using money power etc.,. [Many](#) hold that it is this social messaging that contributed to the box office success of the film. It might be true. Atlee, Director has said, “I am a layman, I am also a part of this society. It is my voice, [it is the audience’s voice, and it is a common Indian’s voice](#).” He denied that he is an ‘anti-establishment’ director.

Burgeoning Indian middle class – the common man – has given Jawan a big thumps up. Does this signify a change in the social and political consciousness of the common man? Not to the extent that they take collective action against the systems that contribute to the social and political issues outlined in the film. [The Indian middle class must rank as one of the most aspirational classes in the world.](#) They encounter corruption, poverty, collusion between business class, bureaucracy and politicians. Yet, they do not have time or inclination to engage in collective action to change the systems. What they need is a ‘super hero’, who could deliver what they themselves cannot do. It is this Atlee and Shah Rukh Khan have provided through the film Jawan.

Shah Rukh Khan becomes the real strongman and avenger of justice and takes on the corrupt and the powerful, distributes money to distressed farmers and ensure prompt upkeep of government hospitals. To execute justice, Shah Rukh Khan builds a vigilante group from among the women prisoners and the audience accepts it as probable. Indian middle classes get their vicarious satisfaction that the problems are getting resolved.

This vote bank, who aspire for the strong avenger, is something Indian political parties cannot afford to loose. [BJP, Congress and AAP](#) defended the film. BJP national spokesperson Gaurav Bhatia in his tweet thanked Shah Rukh Khan “for exposing the corrupt, policy paralysis ridden Congress rule from 2004 to 2014 through #JawaanMovie, reminds all viewers of the tragic political past during the UPA government.” The Aam Aadmi Party claimed the dialogues of Jawan are what Arvind Kejriwal has been saying all along.

The Film Jawan, fits into India’s contemporary national psyche.

PS: _’Common man’ took AAP to power in 2013 and BJP in 2024 on issues like those raised by Atlee and Shah Rukh Khan in Jawan. Can Congress project a superman for the 2024 election?_

‘Dhoomam’ – An Ethical and Logical Dilemma for the Viewers

Reports indicates that people are reluctant to sit through and watch the film, ‘Dhoomam’ in its entirety. The film was screened for three of us in a theatre in Noida, Uttar Pradesh.

‘Dhoomam’, meaning smoke, is meant to be a film to make people aware of the health risks involved in smoking cigarettes and the devious ways in which the manufacturing giants invokes people into the habit of smoking through misleading advertisements and introduction of innocuous looking new products.

Film is the Malayalam entry of the celebrated Kannada film director Pawan Kumar, who has to his credits films Lucia and U Turn. Pawan Kumar is also the script writer of Dhoomam. The producer of the film is Hombale Films, who has under their production list, films like K.G.F. and Kantara in Kannada, both big successes at the box office.

The cast of ‘Dhoomam’ includes veteran actors in film industry Fahadh Fazil as Avinash, Aparna Balamurali as Divya, Roshan Mathew as Sid in the lead roles supported by others like Joy Mathew as the political leader.

Despite the coming together of these celebrated crew and cast, and the good performances by the actors, the film does not seem to be doing well at the theatres.

One reason, as has often be written about, for why the film failed at the box office is that the script has failed to elicit the thriller dimension of the story line and that the dialogues are devoid of sharpness and punch. Overall, this leads to a loss of momentum and excitement, especially after the first half. This criticism is a valid one.

Besides this criticism, there are a few other issues that pull down the impact of the film and distract the viewers from an engrossing participation. One, the film fails to communicate effectively the negative health consequences of smoking. The film is more about how tobacco companies hoodwink general public using innocuous looking and compelling advertisements to cajole individuals in millions towards cigarette smoking and in this process, they make money. We are made witnesses to the dramatic Board Room drama. Though intriguing, those have not resulted in a conversation with the conscience of the viewers about the impacts of those decisions would have on their health situation. Only exception is the narration of the death of a child, a passive smoker, a victim of the smoking habits of the child’s mother. The film also indicates collaboration between tobacco companies and political elites and how global trade relations are manipulated to suit the interests of tobacco companies. However, none of these have been convincingly portrayed.

Another major constraint is the ambiguity in the depiction of the villain. Who is the villain? The tobacco company and the CEO? Or the political establishment? Or Avinash, who helps the tobacco company to hoodwink youngsters and general public into smoking habit through his creative advertisements? Or is it the ‘incognito’ who haunts Avinash and finally culminate in the termination of the life of Avinash and his innocent wife, Divya?

The villainous characters have been depicted conveying contradictory messages in the film. These messages confuse the viewer making them incapable of recognising who the real hero or the villain is and empathising with either of them. Avinash realises the impact of his advertisement strategies on the increasing consumption of cigarettes, growing business for the company, collaboration potentials with international business companies to introduce dangerous addictive substances etc. The movie develops around how a transformed Avinash has been chased down by the ‘incognito’, whose child apparently died as a passive smoker and who blames Avinash for the debacle. The ‘incognito’ exterminates not only Avinash but also contributes to the death of the Divya, who does not have even remotest culpability in the tobacco consumption by the people in general. Divya succumbed to a bomb the ‘incognito’ had planted on her neck, which would burst, if she had stopped smoking. Who will a viewer empathise with as a villain or as a hero – with a sensitised Avinash or an ‘incognito’ who takes moral high ground and pursue the path of annihilation?

This is also true with respect to tobacco company magnate and the political leader. While the political leaders’ culpabilities are camouflaged, Sid, the businessman escapes the cudgels of the rule of law despite he killing the aspirational uncle and sustains his evolving trade relationships to introduce dangerous tobacco combinations.

Viewers of the film ‘Dhoomam’ are left with a concoction of ethical and logical dilemma.

Moreover, government has only said, ‘smoking is injurious to health’, government has not banned smoking as illegal. Viewers, most of them would be smokers, do not want themselves to be within the sphere of illegality.

J John

Gully Boy: The Film that Remains at Superficial Subjectivity

J John

Wikipedia informs us that the film Gully Boy directed by Zoya Akhtar has raked in more than Rs.200 crores in the box office. The film, released in February 2019, has received good critical reviews, most of the reviews giving 4 in a scale of 5. While respecting these verdicts, after seeing the film recently on Amazon Prime, here is a slightly different take on the film. This is being done without any disrespect to the original rappers – Neazey and Divine – on whose real life story the film derives it’s plot.

What precisely Gully Boy tries to convey is blurred. The film does not seem to capture the emergence of hip-hop or rap music culture in India. It also does not explore the change the rappers aspire to bring about in their life situations. The film does not objectively explore the context in which a rap as a branch of music would emerge in India. The film has a story but it remains at superficial subjectivity.

The rap music has African roots and these were played by African Americans during the period of emancipation struggles of the African slaves, which culminated in the ‘emancipation proclamation’ in 1853 by Abraham Lincoln, president of United States of America altering the status of African slaves in the south to free individuals. The rapping reportedly merged into hip-hop music and culture in the 1970s at Bronx, New York as a result of cultural exchanges between African Americans and immigrants from Caribbean. They gained freedom and courage from the Civil Rights generation, Black Power and Liberation Movement, and Black Arts Movement to challenge the system and to create an alternative existence, identity and voice. Historically, the hopes and aspirations of the marginalised are ingrained in rapping.

The film makes an attempt to create the situation of the marginalised by focussing on the slums of Dharavi, Mumbai, but fails to derive an organic link between the marginalisation and emergence of rap musicians as rebels and their music as expressions of social, economic and political aspirations.

Rather, the film builds on the character of Murad Ahmed (Ranveer Singh), the elder son of a driver, Aftab Shakir Ahmed (Vijay Raaz) from his first wife Razia Ahmed (Amruta Subhash) and his personal choice to be a rapper. The social and community context disappears, which resurface only as hero worship by the Dharavi community when they celebrate Murad’s victory in the rapping context.

While it must be acknowledged that Ranveer Singh as Murad does not engage in over-acting, it cannot be convincingly say that he gets into the person, physically and emotionally, of a historically exploited and disadvantaged. The display is more of personal angst and lack of confidence and not the character of person afflicted by systemic violence. More awkward is the characterisation of Safeena Firdausi (Alia Bhatt), who is madly in love with Murad, but exhibits emotional imbalances not befitting a medical student. However, one should say that Alia Bhatt effortlessly becomes the character that the director intended her to be. Similarly graffiti, which has been a component of American hip hop culture, has been inserted into the film without organic integration. The street wall writing and painting look more a one-off affair, not evolving from the consciousness of the community and with their participation, but externally introduced by the Berkeley College student ‘Sky’ (Kalki Kochelin).

At the same time, the film has some important social messages to convey, especially on the issue of what trauma and crisis a second marriage could bring to a family living in the constrained space in urban slums. The film, through characterisation of Safeena, also indicates to the need for addressing restrictions on freedom of choice and mobility girls living in religiously and social mandated life-style restrictions, even among those from the upwardly mobile. Further, the film hints at the living experience of natural communal harmony in Dharavi where all communities live together, when Murad joyously accepts ‘tilak’ on his forehead as an appreciation for his victory in rap contest.

More importantly, the film breaks gender stereotypes. Women in the film tend to break free of shackles created by the society and the system. Women challenge, take initiatives and look for avenues of freedom. This is the case with Murad’s mother, Razia Ahmed (Amruta Subhash), who valiantly challenges her husband Aftab Ahmed (Vijay Raaz) on his second marriage of a lady probably younger than their son and move out of the house with their elder son; with Safeena who engages in a brawl with the suspected lover of Murad and hits Sky’s head with a beer bottle for the same reason and aspires to be a free bird like other girls; and with Sky who gives the major break for Murad, the rapper.

The Gully Boy, as in the case of other such films like ’Slumdog Millionaire’, is predictive. More than that, it does not demand any self examination or accountability from the viewer. The onus is on the protagonist and when the protagonist achieve his/her dreams, the middle class viewer gets vicarious satisfaction. My burden is over, he/she has achieved the dream. The film relieves the viewer from an existential dilemma and/or a political responsibility. On the other hand, for the slum dog, the housemaid, or the driver, the film does two things. One, the film is a moment of self-deprecation – despising the ‘work’ that you are engaged in, be it as a driver, housemaid or mechanic. Two, it gives a false consciousness – looking forward to that golden moment or confluence of moments that will lift you away from the ‘demeaning occupations’ that you are engaged in.

Nevertheless, Gull Boy stands out from the usual Bollywood films and it is worth watching.

20 August 2019

The missing ‘worker’ in Budget 2022 and its implications

Two popular words — ‘worker’ and ‘labourer’ were absent in the finance minister’s speech. This signifies a paternalistic approach to workers where workers are not holders of any legitimate rights over re-distributed wealth.

By J John

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s speech while presenting Budget 2022 is littered with words, ‘jobs’ and ‘employment’. The words reflect the core ideological position of the budget. What is being conveyed is that large-scale budgetary provisions for capital investments will facilitate higher GDP growth, which in turn will bring jobs and employment, thereby increasing income of the poor.

The political economy of this trickle-down theory was again articulated by the Prime Minister when he explained to his party cadres the intent of the 2022–23 Union Budget, the following day. He said, ‘This budget is full of new possibilities for infrastructure, investment, growth and jobs.’

Both—worker as well as labourer—should have found their place at least as a corollary to two other words which have found such prominence in the budget speech. The word ‘job’ and its synonym ‘employment’ each appear six times in the budget speech. The words ‘job’ and ‘employment’ are not peripheral, but reflect the core ideological position of the budget that large-scale budgetary provisions for capital investments will facilitate higher GDP growth, which in turn will bring jobs and employment, thereby increasing income of the poor. The political economy of this trickle-down theory was best articulated by the prime minister when he explained to his party cadres the intent of the 2022–23 Union Budget, the following day. He said, ‘Along with strengthening the economy, this budget will create many new opportunities for the common man. This budget is full of new possibilities for infrastructure, investment, growth and jobs.’

Recurring promises of ‘jobs’/’employment’

In her budget speech, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman explained one by one, how her priorities in budget allocation will generate jobs/employment opportunities. She said, ‘…Productivity Linked Incentive in 14 sectors for achieving the vision of AtmaNirbhar Bharat has …potential to create 60 lakh new jobs’. (p. 2) PMGatiShakti, a National Master Plan for infrastructure development, launched by the Prime Minister on October 13, 2021, has been given tremendous importance in the Budget speech. The finance minister says that the seven engines, namely, Roads, Railways, Airports, Ports, Mass Transport, Waterways and Logistics Infrastructure working in unison will lead to ‘…huge job and entrepreneurial opportunities for all, especially the youth’. (p. 3)

The finance minister also declared that the Credit Guarantee Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises (CGTMSE) scheme will be revamped with required infusion of funds, which ‘will facilitate additional credit of ₹2 lakh crore for Micro and Small Enterprises and expand employment opportunities’. (p. 7) The government site points out that there are an estimated 26 million micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in the country providing employment to an estimated 60 million persons.

Sitharaman indicates ‘…telecommunication in general, and 5G technology in particular, can enable growth and offer job opportunities.’ Similarly, she emphasizes, ‘Investments in circular economy will …help in productivity enhancement as well as creating large opportunities for new businesses and jobs.’ (p. 14) She justifies that Artificial Intelligence, Geospatial Systems and Drones, Semiconductor and its ecosystem, Space Economy, Genomics and Pharmaceuticals, Green Energy and Clean Mobility systems have immense potential to assist sustainable development at scale and modernize the country and will ‘…provide employment opportunities for youth’. (p. 15)

For the finance minister, ‘capital investment helps in creating employment opportunities, inducing enhanced demand for manufactured inputs from large industries and MSMEs, services from professionals, and help farmers through better agri-infrastructure.’ (p. 17) Same is the case with National Capital Goods Policy, 2016 which ‘would create employment opportunities and result in increased economic activity’. (p. 26)

Income inequality in India

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman is keen to justify each of her major budgetary investment priorities by arguing that those will generate jobs/employment. It will be equally hypothetical to counter argue that the actions will not. A better strategy would be to look at the experiences in the past. It is an established fact that India is among the high-inequality nations. Chancel and Piketty (2017) observe that India comes out as a country with one of the highest increase in top 1 per cent income share concentration over the past thirty years. According to them, growth has been highly unevenly distributed within the top 10 per cent group since the early 1980s, revealing the unequal nature of liberalization and deregulation processes. These findings are also substantiated by the Credit Suisse and Oxfam reports. The Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2018 has observed that the richest 10 per cent of Indians own 77.4 per cent of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 60 per cent, the majority of the population, own 4.7 per cent. The richest 1 per cent own 51.5 per cent of the wealth. The Oxfam report ‘Inequality Kills (India Supplement)’ released in January 2022 captures the dynamics of wealth inequality during the pandemic years. As per the report, while 84 per cent of the Indian households saw their income shrinking during the pandemic, the corporate profits have soared wherein the profits of the top 500 companies grew at a record 75 per cent. The report states that the richest 98 Indian billionaires had the same wealth (US$ 657 billion) as the poorest 555 million people in India, who also constitute the poorest 40 per cent of our country. The 2022–23 Budget espouses the trickle-down theory that, in addition to being a misnomer, is impractical.

Importance of ‘worker’ identity

It is not the job creation or employment generation alone, but the quality of employment generated and its income re-distributive capacity that matter more. In this context, the excuse of the absence of the term ‘worker’ or its synonym(s) becomes clearer. The term ‘worker’ has its historic subjective, social and political dimension along with its objective dimension as a part of the production system. The words, ‘job’ or ‘employment’ need not make a distinction between employment in the MSMEs or the organized sector; the question of the nature and quality of jobs is secondary or immaterial.

Worker identity is collective in nature as opposed to the atomistic inanimate identity of job or employment. The collective identity—working class identity—enables workers to gain a sense of their rights vis-à-vis the entrepreneur to whom they sell their labour power as well as the state that provides and governs policy and institutional framework. Worker identity brings in trade unions, the organizations of and for the workers, as a stakeholder in the economic activity.

Recognition of those in employment as workers increases the accountability of the state as the custodian of their rights, in particular the realization that economic justice happens only when the state undertakes policy measures that ensure an equitable distribution of the wealth generated in the economy. Annual budgets provide opportunities for the government to set the policy framework to create and redistribute wealth among workers and the people of India, rather than its accumulation in the hands of a few. This is precisely what Sitharaman refused to do. Consider three contexts.

Labour codes not mentioned

First, the Union Government has brought in Labour Codes. Labour codes by their definition are laws that codify the rights of workers. The budget while talking about job creation as an inherent objective of capital investments did not discuss how the Labour Codes will have a place in the interface between the capital and the labour and what the associated cost implications are. It is important to note that jobs and employment as statistical figures, and ease of doing business in itself need not uphold labour rights. The budget merely seems to bring in statistical projections without acknowledging the rights of the worker.

Wages does not find a mention

The second context is the issue of wages. It is the primary channel through which the re-distribution can happen by providing ‘living wages’ (Article 43 of the Indian Constitution) to the workers who contribute to the generation of the wealth. In 2018–19, around 81 per cent of the workforce was employed in enterprises with less than 10 workers, or in the unorganized sector by definition, for whom a regular salary with attendant social security benefits was not available. The principle of payment of Minimum Wages was applicable for them. The Code on Wages, 2020, which subsumed various wage laws (Minimum Wages Act, 1948; Payment of Wages Act, 1936; Payment of Bonus Act, 1965; and Equal Remuneration Act, 1976) proposed a National Floor Level Minimum Wage (NFLMW) below which the wages should not fall. The Expert Committee (2019) constituted by the Government of India recommended a national minimum wage to provide a decent standard of living and meet the basic needs, including education, food and healthcare, proposed ₹ 375 per day (or ₹ 9,750 per month) irrespective of sectors, skills, occupations and rural/urban locations. As per the 2019 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data, approximately 58.5 per cent of self-employed workers reported monthly earnings below this threshold. For casual workers, the share at 88.5 per cent was even higher (State of Working India 2021). Moreover, no notification on National Floor Level Minimum Wage has been issued by the Government of India. Behind the hullabaloo about job creation, the 2022–23 Budget shied away from taking even a baby step towards the re-distribution of wealth being generated in India by clarifying its position on wages.

Social security does not find a mention

The absence of non-discriminatory social security to all workers, another consequence of the structurally debilitating informality of employment in India, is the third context. The latest PLFS data confirms that the basic characteristic of Indian workers have not changed at all. In spite of regime change at the centre, more than 91.3 per cent of India’s over 430 million workers remain unorganized or informal. The definition for the informal workers as evolved by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector (NCEUS) and now popularized on the e-Shram portal is clear: ‘any worker who is a home based-worker, self-employed worker or a wage worker in the unorganized sector including a worker in the organized sector who is not a member of ESIC or EPFO, or not a Government employee is called an Unorganized Worker’. One’s status as an informal worker is determined by the fact that as a worker whether you received social security benefits from either Employees State Insurance Corporation or from Employees Provident Fund Organization, even if neither of them are substantially funded from the consolidated fund of India. Besides the absence of a living wage, the non-existence of state-funded social security benefits for the workers, is another reason for the existence of the chronic inequality in India.

The Code on Social Security 2020 which received Presidential assent on September 28, 2020 announced the extension of social security benefits to workers in the unorganized sector, platform workers and gig workers. Although the code on social security talks about the creation of a social security organization and allocation of funds at the central and state levels for the execution of social security schemes, there has not been any notification to those effect.

Meanwhile, the e-Shram portal, launched by the Ministry of Labour and Employment on August 26, 2021, that intends to create a centralized database of all unorganized workers to be seeded with Aadhaar has been highly pitched. The e-Shram purportedly is for better execution of various social security schemes for the workers in the unorganized sector. To begin with, after registering, the worker will get an accidental insurance cover of ₹2 lacs under the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (PMJJBY). The website of e-Shram says that ‘in future, all the social security benefits of unorganized workers will be delivered through this portal.’ However, there is no clarity about the social security rights available to the workers registered at the portal.

e-Shram can be seen as the most systematic effort in recent years to institutionalize the duality of Indian labour between the organized and the unorganized that aims to apportion differential rights to the workers. Nevertheless, if the government has to go ahead with the idea of social security for unorganized workers, there should have been a corresponding financial allocation. The e-Shram budgetary allocation is just ₹ 500 crore for FY 2022–23. This again demonstrates the lack of will on the part of the government towards re-distribution of wealth being generated in the country, thereby exacerbating the chronic income inequality.

Conclusion

The absence of the word ‘worker’ in the finance minister’s budget speech demonstrates a ‘capitalist’ approach, as former Finance Minister P. Chidambram has called it, to wealth creation oriented towards the super-rich. It signifies a paternalistic approach to workers where workers are not holders of any legitimate right over a re-distributed wealth.

The Ghosts in the Hills: The Story of Maoism in Nepal and a Rebellious Womanhood

Book Review (Krishna Upadhyaya, The Ghosts in the Hills, April 24, 2021, pp.359, Kindle Edition) Accessible at https://www.amazon.com/Ghosts-Hills-Krishna-Upadhyaya-ebook/dp/B092TH7JX2?asin=B092TH7JX2&revisionId=4b0209b9&format=1&depth=1

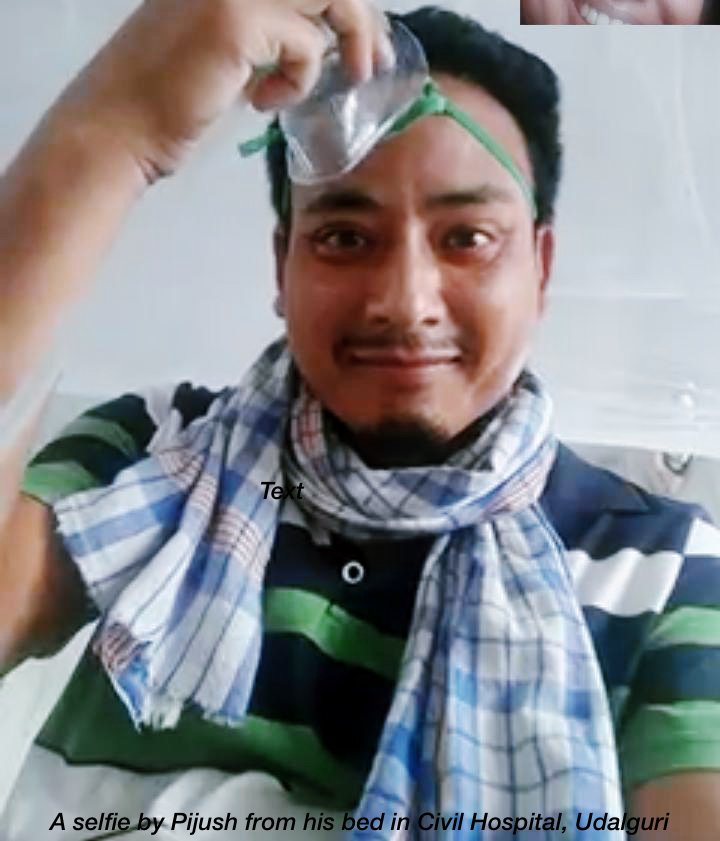

Pijush Goyary: Indomitable Spirit that COVID Cannot Take Away

Pijush Goyary was all of 33 years. COVID-19 preferred to take him away physically from us yesterday (2 June 2021) afternoon. Pijush did not have any co-morbidity. He was quite a healthy person.

From Kokrajhar, he lived in Tangla, Udalguri district, Assam along with his wife, Sophia Goyary and a 3 year-old son. On 23rd May he called me to say that he was having throat pain, constant cough, fever, body pain and loose motion. He tested positive along with his son. Child was alright within two days. He consulted Doctors online and took medicines. But, Pijush’s cough worsened, fever persisted and he started feeling breathless on 26th May. He decided to get admitted to Udalguri Civil Hospital, but had to wait till late in the evening to get an ambulance. In the hospital he was put on Oxygen. On 27th May, after check-up, Doctors said that though he was outwardly strong, his lungs were affected and his other parameters are not good. They took steps to shift him to a hospital with better facilities.

Pijush wrote, “today, I was very tired, totally couldn’t sleep, after injections I was dead hungry, on the other hand restless cough, and mask in mouth.. the moment was so funny.. so I decided to remain awake. I will rest full afternoon hours, as cough doesn’t disturb during the day.. much.”

Pijush is Bodo. To keep him engaged, I asked him, “what about collaborating to work among Bodo women on traditional weaving practices?”

He was quick to respond, “the idea is fantastic, if we really launch it …Sophia also has great interest in designing …so let’s discuss.”

Pijush was a peoples’ person. He had a natural inclination towards livelihood centric activities. Pijush, fresh from his Post Graduation in Social Work from the University of Pune, started working among small tea growers in the Bodoland districts of Assam in 2011. It was a value chain intervention aimed at ensuring fairer terms of trade for small tea growers by collectivising disjointed farmers, empowering them at various levels to take on higher nodes in the tea value chain. Five years of his work in Bodoland resulted in increased bargaining capacity of small farmers as collectives and overall increase in price for green leaves. Pijush continued to work among a selected set of collectives who decided to move further up the value chain by setting up own manufacturing units and a marketing company with the objective of ensuring a share of profit to farmers from multiple stages of value accruals. He did this without a regular income for about four years. Pijush had empathy, he had vision, he had strategy and he was an optimist.

On 28th May, by 4:00 AM his ambulance reached Tezpur Medical College. Pijush wrote, “… very hot and sweaty. However, it is seen that staff are much talented, they observed many things in my health, put me on more new medicines, marked star on my prescription …and ordered to use bucket for urinal and avoid common toilet.” On the same day, he was put on non-invasive ventilation. That was the end of my communication with him.

Pijush was loved by his team members and they contributed in multiple ways. In particular, Shampa Das and Joy Chakravarty, became active and mobilised support for him in the hospital. Pijush was closely monitored by a team of Doctors. However, his oxygen level was fluctuating and his lungs damaged due to acute Pneumonia. Doctors debated whether he be put on intubation.

Pijush collapsed yesterday afternoon. None was with him, he being in the ICU. His brother and Sophia’s mother who were outside the ICU were informed of his death. Sophia was at home in Tangla, she herself a COVID-19 patient, taking care of her son, her sister and her father, all COVID-19 positive.

Pijush’s body was brought to Tangla, late in the evening. Accompanying him was his brother, Sophia’s mother and two persons from the hospital. The night curfew in Udalguri district and the area of Pijush’s residence being a containment zone, none could be present there to bid him farewell as his body was lowered to the grave in the cemetery of the Church.

Nevertheless, Pijush’s legacy lives on and there is an air of determination that his vision will not be lost.

Jai Singh – Unflinching Compatriot of Bonded Labourers in their Struggles for Liberation

Yesterday (22 May 2021) morning, when I received the message that Jai Singh was no more, I felt extremely guilty. The reason for my remorse was, despite wanting to talk to him, I had not called him.

Jai Singh devoted his entire life for the liberation of bonded labourers in agriculture and brick kilns. As in the case of a large number of youth all over the country, Jai Singh became an activist in response to the call for ‘Sampoorna Kranti’ (total revolution) by Jayaprakash Narayan in his mobilisation against the authoritarian tendencies shown by Indira Gandhi in the 1970’s and the declaration of ‘Emergency’ in 1975. He was part of a group of young people, led by (Late) Swami Agnivesh, to form Bandhua Mukti Morcha (Bonded Labour Liberation Front) in 1981.

There was growing realisation in the 1970’s of the existence of extreme bonded employment relations in different forms in the agrarian sector in India – ‘sepadari’ or ‘sajhi’ system in Punjab, ‘siri’ in Haryana, ‘halipratha’ in Rajasthan and Gujarat, ‘jita’ in south of India and ‘gotia’ in Bihar. It entailed a worker mortgaging his labour power and freedom to the landlord in exchange for money he has taken as loan. Unable to pay back the money, the debt bondage extends to his entire family and for generations. Similarly, in the brick kilns, workers – both migrant and local – are obtained through contractors, who pay some money in advance and against which the whole worker households will have to mortgage their labour power and freedom during the year and subsequent years, if the money not repaid.

In 1985, with the objective of working among bonded labourers in agriculture and brick kilns in Punjab, he established Volunteers for Social Justice (VSJ). Debt bondage in the agrarian sector in Punjab saw a reduction as a result of fundamental changes in land ownership patterns and employment relations brought about by the adoption of green revolution, mechanisation of farming processes etc,. Jai Singh and VSJ largely concentrated his energies in addressing the problems of bonded labourers in the brick kilns of Punjab and adjoining areas.

Jai Singh followed the classical mode of combating debt bondage in India, which consisted of the triple strategies of identification, release and rehabilitation. The classical mode is the prescription ingrained in the Bonded Labour System Abolition Act (BLSA), 1976, which Indira Gandhi adopted during Emergency at the initiative of a group of sensitive bureaucrats.

Of these, his focus was more on identification and release of bonded labourers in brick kilns. He moved a step further and combined strategies of legal fight, mobilisation and struggle, which made his approach unique, popular, participatory and intense.

He invoked the power that the BLSA vests on the social action groups and the District Magistrate in the identification and release of hundreds of bonded labourers (Neeraja Chaudhary Vs State Of M.P. on 8 May, 1984 CITATIONS: AIR 1984 SC 1099). His team included lawyers who took up the matter at the District Court. Though the the BLSA does not provide for an appeal because the District Magistrates are the first and last authority in determining bonded labour, he challenged their reluctance by making appeals at the High Court of Punjab through Writ of Habeas Corpus and approaching the National Human Rights Commission. The VSJ has produced two volumes of such case files giving tremendous insights into his legal mind and strategies. A second important premise of his legal fight was that brick kilns are factories as defined under Factory Act, 1948 and therefore, workers in brick kilns are eligible for all rights any factory worker would enjoy including regular wages, safe working conditions, non-discrimination between men and women, discontinuance of piece-rate wages, safety and health at work and right to organise and collective bargaining. Most of the legal fights were for payment of wages because the non-payment or delayed payment of wages were the instruments that sustained debt bondage.

Jai Singh, beyond adopting legal strategies, mobilised brick kiln workers and engaged in powerful agitations. To give an example, based on repeated complaints by VSJ team, the Sub-Divisional Magistrate, Mansa district, declared workers free in a brick kiln located in Village Dharampura, Mansa District on 10 March 2014 and ordered their release with payment of unpaid wages and transportation to the railway station on the employer’s expenses. On 13th March, at the railway station, henchmen of the employer snatched wages from workers. VSJ team, staged a protest along with hundreds of workers and activists on 14th March 2014 at the railway station, laid down on the railway tracks and refused to get up. Police managed to return the wages to the workers and a case was registered against the employers.

VSJ has a sister organisation, Dalit Dasta Virodhi Andolan (Movement of Dalits Against Slavery). Punjab has the highest percentage of Scheduled Castes in the population (32 per cent) in the whole of India. The local workers engaged in the brick kilns are overwhelmingly Dalits and Jai Singh understood the importance of the caste identity in the mobilisation of workers, especially in the context of mobilisation history of Dalits in Punjab along Deras. Moreover, DDVA helped him to transcend the constraints of working within the framework of a registered society.

Jai Singh had a universal approach despite his deep rootedness. He collaborated with national and international organisations within the framework of fundamental rights and principles at work and universal human rights.

I have had opportunities for close collaboration with him and activists of VSJ and DDVA in our joint struggle against debt bondage in India.

He had the habit of inviting his friends to his house and entertaining them with sumptuous Punjabi non-vegetarian food and drinks. I recall once, we went to a local market on the way, bought big fish, got it cooked by the vendor and carried it all the way to our place of stay in Amritsar.

It was my unnecessary hesitation that created a situation that will keep me discomfited for the rest of my life – that I couldn’t talk to him before he left us.

Jai Singh reminds me there is lot more than minor differences in perspectives in the days of pandemic when nobody knows who goes next.